Here are a few things we know about Ghana's 2012 elections.

It's going to be close. With 168 of 275 constituencies reporting, incumbent John Mahama has 49.83% of the vote and his chief rival Nana Akufo-Addo has 48.68% of votes. That's lots closer than polls, which predicted a victory for Mahama, had been suggesting. Given that the third party candidates have less than 2% of the votes, a run-off seems possible, if both Mahama and Akufo-Addo remain below the 50% mark.

It wasn't perfect. This was Ghana's first election with a new biometric voter identification system. A massive registration drive issued voter ID cards that include information on the bearer's thumbprint. Voters present their card, verify their thumbprints and are then able to vote. This system malfunctioned in some locations, leading to long lines and hot tempers, and the electoral commission extended voting into today to ensure everyone can exercise their franchise.

One of the reports I read yesterday on Twitter suggested that some of the people having bad problems were people who work with their hands, suggesting that scars or blisters might be interfering with the scanner. An article today offered advice on cleaning hands using Coke or akpeteshie (locally distilled sugar-cane or palm wine liquor) to create more readable prints.

Ghana invested heavily in biometric systems because there's understandable concern about voter fraud. The 2008 election was settled by less than 40,000 votes and there was widespread concern that voters were sneaking across the border from Togo to vote, or voting multiple times. Stories like this one, in which biometric machines are revealing multiple attempts to vote, are getting good play in Ghanaian social media. (Great article, from the headline that implies a Robocop-style machine arresting the miscreant to descriptions of the gentleman's alacrity in eluding authorities. :-) Given successes like this one, it's likely that biometric voting will continue, with some fine tuning, in subsequent elections.

It was pretty damned impressive. Ghana has had a series of increasingly credible elections, starting in 1992, and capturing international interest in 2000, when a free and fair election ousted the party of former dictator (and later democratically elected leader), Jerry Rawlings. 2000, you may remember, was the year of endless Bush v. Gore drama in the US, and my friend Koby Koomson, then Ghana's ambassador to the US, sent me a copy of the letter he'd sent to President Clinton, offering Ghana's assistance to the US in election monitoring.

There's a wealth of articles that celebrate Ghana's successful democracy, including helpful insights from economist George Ayittey, who attributes democratic success to a strong and independent media, a vibrant set of NGOs, and maturity on the part of the nation's politicians, who notes that the 2008 election could easily have turned chaotic, had not Akufo-Addo graciously conceded.

What's interesting for me, as a passionate Ghanaphile, but an outsider to the political process, is that watching Ghana's elections is a helpful tutorial in global good electoral practices.

The video above, from the Ghana Decides project, shows the vote counting process in one of the poorer neighborhoods of Accra, the historically Muslim neighborhood of Nima. The transparent boxes, the public sorting of ballots and the crowd watching the process are all parts of an intricate system that helps remove uncertainty from the results.

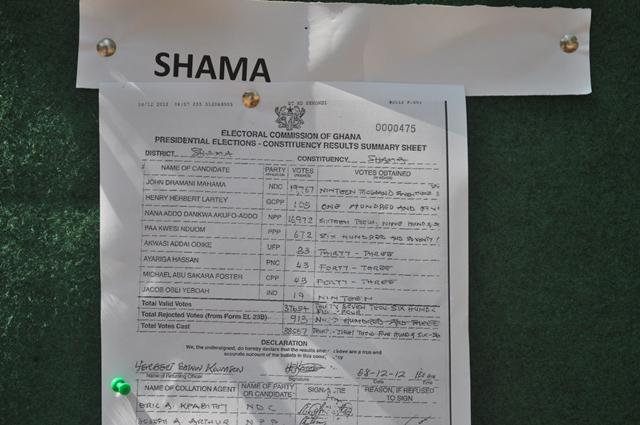

So are images like this one: the results from a specific polling place, publicly posted. In Zimbabwe's last presidential election, posting these votes allowed the opposition ZANU-PF to conduct a parallel vote tabulation and contest MDC's assertions that they had won outright. Parallel tabulation efforts are underway in Ghana, as well, with multiple monitoring, civil society and media organizations trying to ensure that the electoral commission's results are in line with the reports at tens of thousands of polling places.

I'l be very interested to learn what my friends Mike Best at Tom Smyth at Georgia Tech and the team at PenPlusBytes learn from their experiments in social media monitoring. (Disclosure: I'm on the board of PenPlusBytes, and am advising Tom's on his dissertation.) They've been aggregating tens of thousands of reports via Twitter, Facebook and blogs, and following up on reports of violence or conflict. By monitoring Ghana's peaceful elections, they hope to establish best practices for using their tools in monitoring more contentious ones, hoping to defuse violence before it unfolds.

I'll offer two disappointments in Ghana's elections. One is that Ghana continues moving towards being a purely two-party state. One of the benefits of a two-round electoral system (which forces a run-off if no one receives 50% + 1 vote in the first round) is that it encourages people to vote for smaller parties to express preferences, knowing they can vote strategically in a second round. But Ghanaian politics appears to have turned into a battle between NDC and NPP, with few surprises, even when the third party candidates are smart, engaging and adding to the dialog.

Second, NDC and NPP allegiances often have more to do with geography and tribe than with platform. I saw a dispirited tweet last night that suggested the best way to improve your electoral chances was to increase the birthrate in the parties' respective strongholds. It's disappointing to see elections based more on ethnicity than on issues, but it's also clear this isn't the reason behind everyone's vote.

Here's hoping that a close race remains and peaceful one and that Ghanaians continue to have justifiable pride in a robust and transparent electoral system and a healthy democracy.

No comments:

Post a Comment